Federated Learning with NVFlare: A Mental Model for Jobs, Clients, and Servers

A lot of the best ML data is the least portable. Hospitals can’t centralize patient records. Banks can’t ship transaction logs. Phones generate rich signals that never leave the device. Even when data movement is technically feasible, it’s often blocked by privacy commitments, regulation, contracts, or internal friction.

The goal doesn’t change: you still want a model that benefits from patterns across all those datasets. Training each silo independently usually caps performance and generalization. Centralizing creates a long approval chain and a bigger blast radius.

Federated learning is a practical middle path: multiple parties collaborate on training without pooling raw data. NVFLARE is one framework that makes this operational by coordinating training across a server and many clients while keeping training where the data lives.

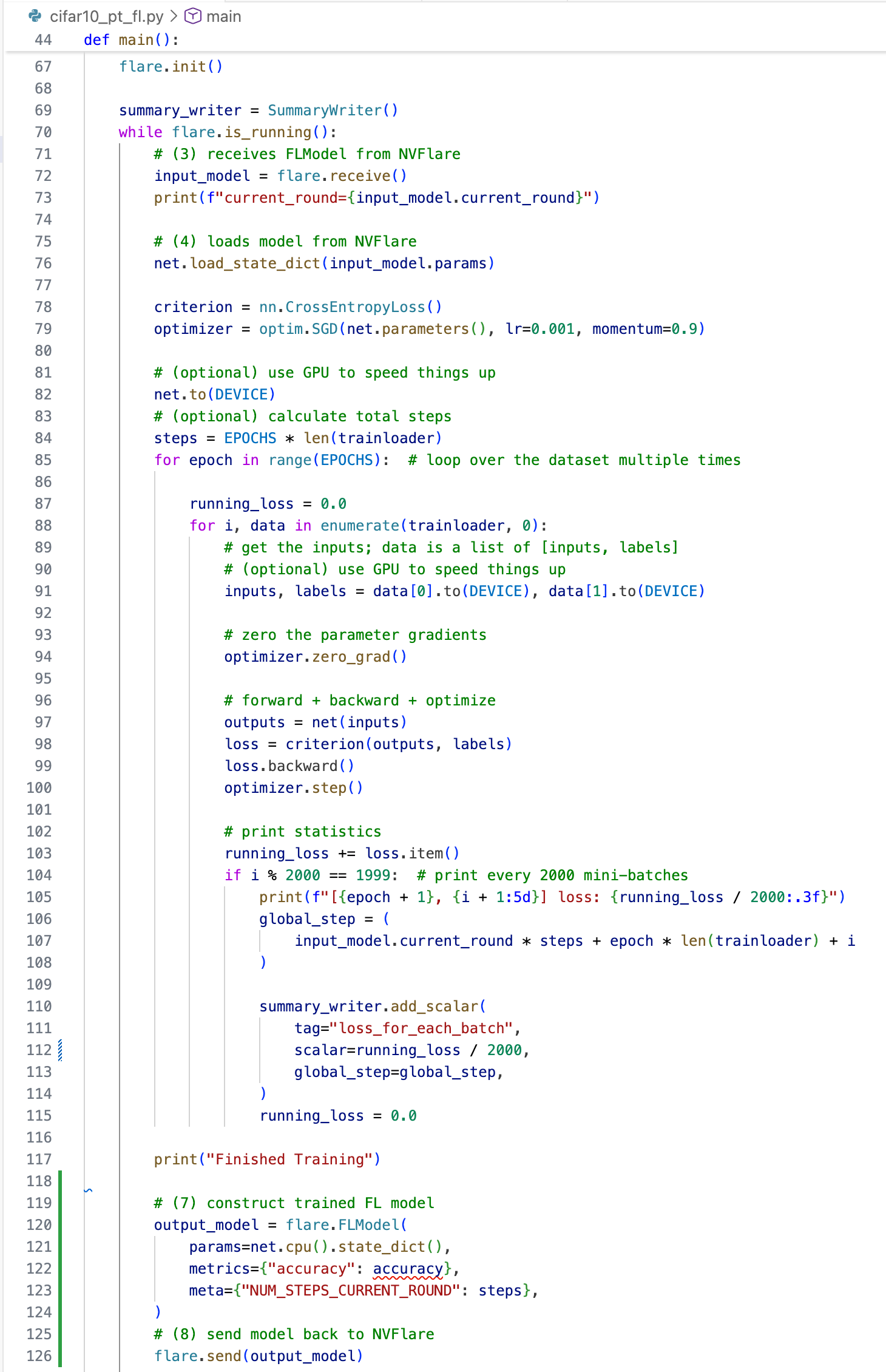

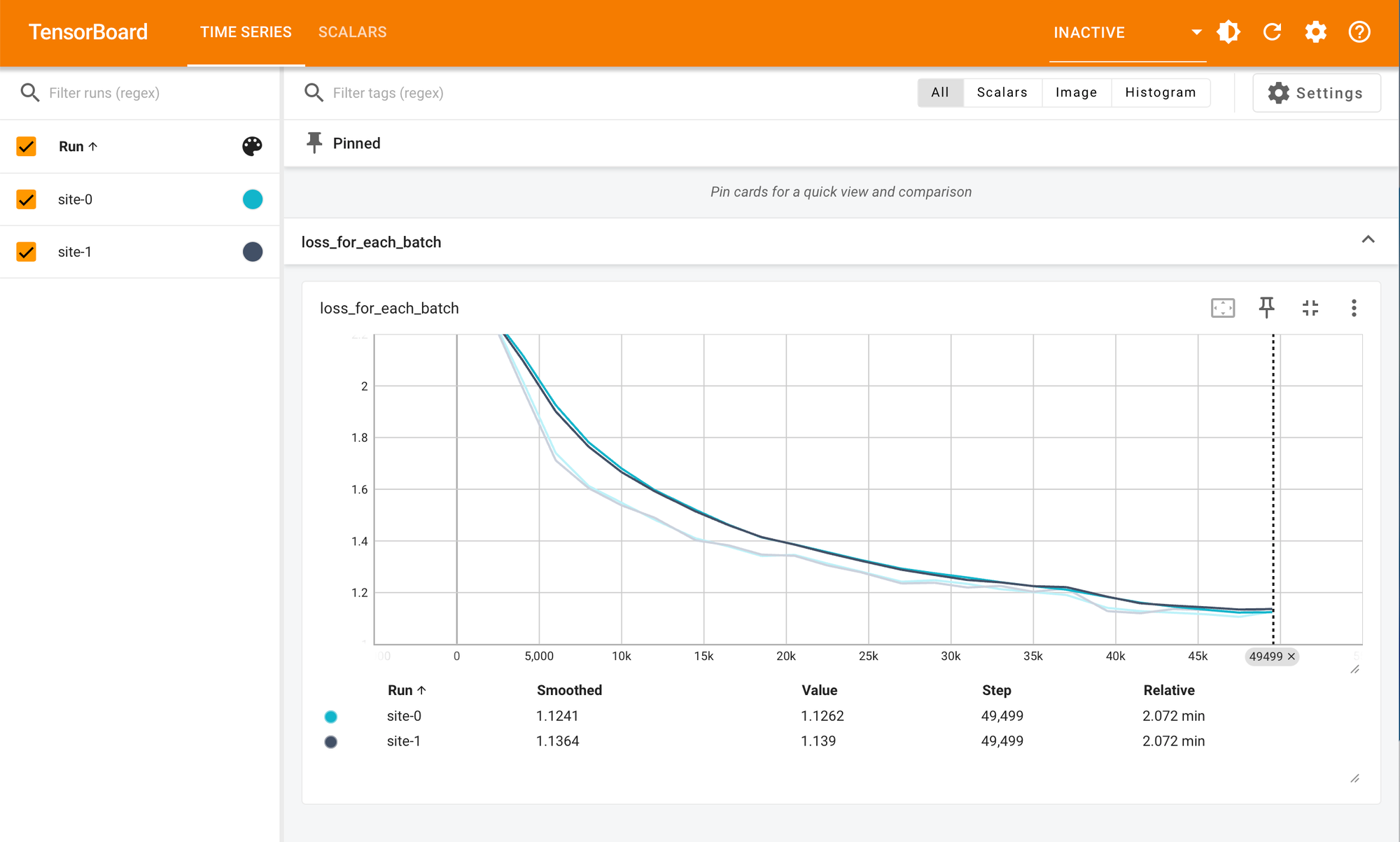

Federated learning in one loop

Federated learning (FL) keeps data on participating sites (“clients”) and exchanges model-related information with a coordinating process (“server”).

A simplified round looks like this:

- Server initializes a global model.

- Server sends the current model (or parameters) to selected clients.

- Clients train locally for some steps/epochs on private data.

- Clients return updates (often weight changes) and metrics.

- Server combines the updates (e.g., weighted averaging) into the next global model.

- Repeat for multiple rounds; optionally validate and log along the way.

NVFLARE, briefly

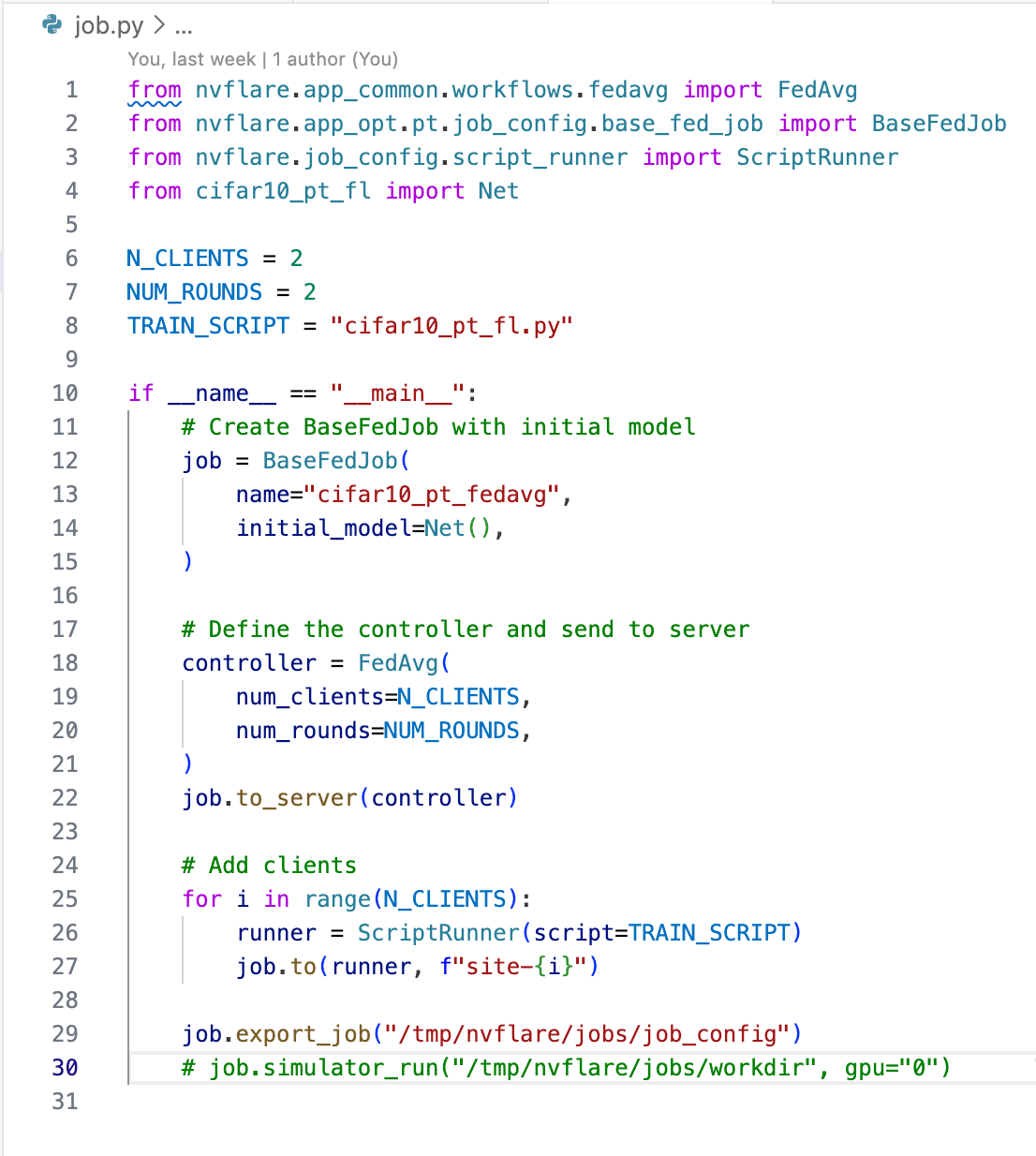

NVFLARE gives you a concrete structure for running federated learning as a coordinated “job” across a server and multiple clients. It standardizes how you package orchestration, local execution, and the artifacts exchanged between them, so FL runs like a repeatable system instead of a bespoke distributed project.

NVFLARE’s mental model: the job is the contract

The simplest way to think about NVFLARE:

An NVFLARE job is a contract between the server and the clients.

It’s the deployable unit you submit, and it’s self-contained:

- what runs on the server

- what runs on the clients

- the configuration that wires them together (roles, components, task names, payload expectations)

This “job-as-contract” framing is what makes federated training repeatable. You’re not rebuilding a bespoke distributed system for each experiment—you’re shipping a packaged agreement about orchestration and execution.

The pieces (plain language)

- Server: the “manager.” It decides what happens each round, sends work to clients, collects their results, and updates the shared (global) model.

- Clients: the “workers.” Each client keeps its data private and runs training or evaluation locally.

- Workflow / Controller (on the server): the server’s playbook. It defines the loop: when a round starts, which clients participate, what tasks get sent, when updates get combined, and whether to run evaluation.

- Executor (on the client): the code that runs when the client receives a task (for example: train for 1 epoch, evaluate, compute metrics).

- Task: a named instruction from server to client, like "train" or "validate". The name is the trigger for what code path to run.

- Aggregator: the “combiner.” It merges client updates into the next global model (often a weighted average; clients with more data can count more).

- Payload: the package sent back and forth with each task. It carries things like model weights (or weight changes) and metrics (loss/accuracy).

Summary

Federated learning addresses “data can’t move” constraints by training across multiple private datasets without centralizing them. NVFLARE operationalizes this with a packaging model that makes coordination explicit and repeatable. The key mental model is that a job is a contract: the server drives rounds and combines updates, clients run training next to private data, and tasks + payloads define the protocol they use to communicate.

Two practical constraints show up fast in real deployments:

- Non-IID data: client datasets differ (population, device, geography, collection process), which can slow convergence or bias the global model.

- Messy systems: clients are heterogeneous, slow, intermittent, and failure-prone—so orchestration and observability matter as much as the math.